That’s not true; I have no actual memory of disposing of the Barbie Dream House, but do know that Barbie did not go the way of her house. She perished on a Saturday in the summer of my sixteenth year.

At dinner that particular Saturday, my mother thanked my father and little brother for cleaning the basement. “It looks so much better,” she said, “with all those boxes gone.”

“What boxes?” I said, not much caring that my father and brother had spent the afternoon cleaning the basement, a despised chore I had escaped solely through the coincidence of an all-day babysitting job, during which I ate the kind of junk food we never had at home, made ten bucks, and talked on the phone to BJ, my first real boyfriend, who called to sing me a song he had written during our recent break-up.

“The boxes that were under the Ping-Pong table,” my mother said.

Or maybe she said “all” – “All the boxes that were under the Ping-Pong table.”

A family of unrepentant and couldn’t-help-ourselves savers, the empty boxes, relics from our move three years earlier, had been stacked and nested and shoved under the Ping-Pong table against the someday when “we might need them.” (The Ping-Pong table itself was one of those things that had outlived its usefulness, evidence of a time when we had actually done things together, of when we had a finished basement rather than bare concrete floors and open wooden steps that shook when we used them.)

But not all of the boxes had been empty.

One, with the flaps carefully tucked each under the other, had been placed there for storage, the handwritten label clearly visible to anyone who cared to look: Barbara’s – Save.” Inside: a teddy bear named either Bobby Jo, Squeaky or Powder Puff, depending on which sibling you asked; a baby doll named Jeannie; a bride doll and her hand-sewn wardrobe that had belonged to my older sister; Tressy, whose black hair grew at the touch of a button; and Barbie.

***

When we had packed for the move from Georgia to Virginia, Mom had discovered the Barbie Dream House jammed behind some bags of old clothes in the garage. She said, “What do you want to do with this?”

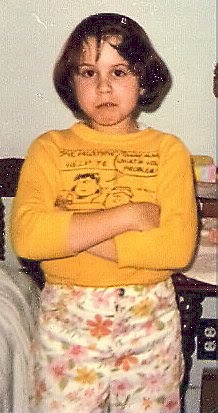

I was thirteen, only two years past the day when the Spivey twins, smug after a day spent swimming with my neighbor, the boy I loved, the boy who belonged to me when we were at home if at no other time – asked if I played with dolls. The dream house’s dusty case brought back all the shame of that day, a shame that was never far away and that was, at that time, manifested in the braids my parents’ economy forced on me (I could only wash my long hair every other day) and the leather, hard-soled shoes necessitated by a skin allergy.

“I said, “Throw it away. Now. Right away. The sooner the better.”

“It’s in good shape. Some other little girl might want it.”

Some other little girl had been the beneficiary of every one of our previous moves, largesse being our parents’ excuse for shedding furniture, old clothes, my older siblings. I sometimes wondered whether Some Other Little Girl got to visit the third grade class my sister taught or spent the night on a cot in my older brother’s living room.

I thought, “Get it out of here, I can’t stand to look at it, can’t stand to realize that I’m still that same geeky girl, that not only is Jeff not my boyfriend but that no one is,” but just said, “Fine, give it to Goodwill,” resigning myself, ungraciously, to its continued presence in the garage.

“What about Barbie?” Mom said. “Don’t you want to save her for your little girl?”

No, I did not want to save Barbie. She had betrayed me by being the things I could never be.

“You might want her someday.”

We don’t know, at eleven or thirteen or sixteen, who we will turn out to be. The things we think we want to be seem inevitable and not merely one possibility out of several, not a path we’ll never take. And so I retrieved Barbie from the house that was almost her tomb, placing her ungently in the box that held my other dolls – all saved for that little girl that I would never have.

I had already wrapped my dolls in baby blankets, their clothes arranged for minimal wrinkling, leaving their faces uncovered. “Barbara’s – Save,” I wrote on the box, and “Do Not Throw Away,” peeled away the tape that held it closed, and stuffed Barbie inside. Maybe one day I’d be able to face her again – when I was older, prettier, no longer bound by my parents’ restrictions against clean hair, shaved legs, makeup.

***

And so now I said, “All what boxes? My dolls were down there.”

“We didn’t see any dolls,” Dad said.

My voice rose. “The box was under the Ping-Pong table. It was marked. It said, ‘Do Not Throw Away.’”

I threw down my napkin and shoved the wooden bench that had been my grandmother’s backwards, heedless of its age,

Hey, watch the chair

running down the steps with a haste my fear of heights usually constrained

followed by my mother, They're not there

unwilling to believe

I'm so sorry

but the floor beneath the Ping-Pong table was bare, clean, no sign of a big cardboard box marked “Barbara’s – Save,” and I collapsed on the bottom step, weeping, one hand still clutching the railing my legs incapable of holding me up unable to breathe stunned by the irrevocability of loss.

Mom, distraught, kneeling behind me, arms around me, weeping too.

Dad at the top of the steps, They were just dolls.

Mom turning on him in fierce defense of the heartbreak she had orchestrated, Call the dump. See if anyone's there.

Phone calls to the county: who was responsible for the landfill, who could we talk to? A real person on the other end, despite the weekend: The guy who works on Saturday, he really smashes things down. Any other day and you'd probably be okay. You can go look, but you probably won't find anything, Mom pushing us into the car, me with my unwashed face, Dad and Bryan protesting, Can't we wait until after dinner?

Couldn't you see that one of those boxes wasn't empty?

Dad, You told us to take everything.

Mom, guilty, quick to shift blame, Why didn't you look?

Me, sixteen, needing no provocation to blame parents for everything.

Mom, Maybe it's not too late

and hope, unfairly, revives only to die again when we saw the ground was indeed smashed, big tire tracks covering all. Still we searched, stumbling over hillocks and furrows, fearing and hoping for a sign of pale skin, a lock of bright hair.

“They aren’t here,” I said, but Dad said, “Let’s just keep looking. Maybe he missed it. Maybe there’s just dirt on top of the box.” My heart couldn’t stand the thought of their broken bodies and I wanted to go.

Then BJ appeared, loping up the road toward us – tight, curly hair, white T-shirt, jeans – his presence so unexpected I could not take it in. My parents did not like him – he smoked, he had a car – and thought he was a delinquent in the making. (Not true. He was, and remains, one of the most considerate, respectful, and honorable men I know.)

What was he doing there?

My mother’s voice across the phone lines, pushing him as she’d pushed us – Go, go, they're at the dump, she's crying – probably the only time she ever sent a boy to me, the only time she ever acknowledged my need for someone else. Family watching or no, I went to him, right to him, no questions about whether I felt the same way he did or what I wanted from the relationship or what other people thought. All I knew was that someone loved me, someone whose concern was uncomplicated by hunger or annoyance or guilt.

Barbara, This piece just throbs with pure instinct. I like the stream-of-consciousness techniques you used to unfold the story and conversation. I particularly liked the line "...someone whose concern was uncomplicated by hunger or annoyance or guilt." Wow! Not too many of those people in our lives, are there?

ReplyDeleteI too shared the narrator's angst at not being done wanting to play with the Barbies and not having others know I still wanted to. Do you think it was the writer in us? We wanted to make stories with them? I don't know, but mine disappeared too. My mother gave them to a younger cousin when I went off to college. I think she asked me first, but when I hesitated, she prodded. A few years ago I wrote my cousin and asked for them back, and so got some things returned, particularly outfits my mother had sewn, which meant at least as much as the dolls.

This reminds me of a prompt I used in a writing group that was very successful: What one lost thing from your childhood would you most like to find and why? Beautiful stories! I think that group that day felt closer to each other after sharing their responses to that prompt than any other time I've facilitated.

I love the prompt.

ReplyDeleteI think playing with Barbie did have a lot to do with storytelling. That's what I did--I narrated her life while I played, whether I was alone or playing with friends.